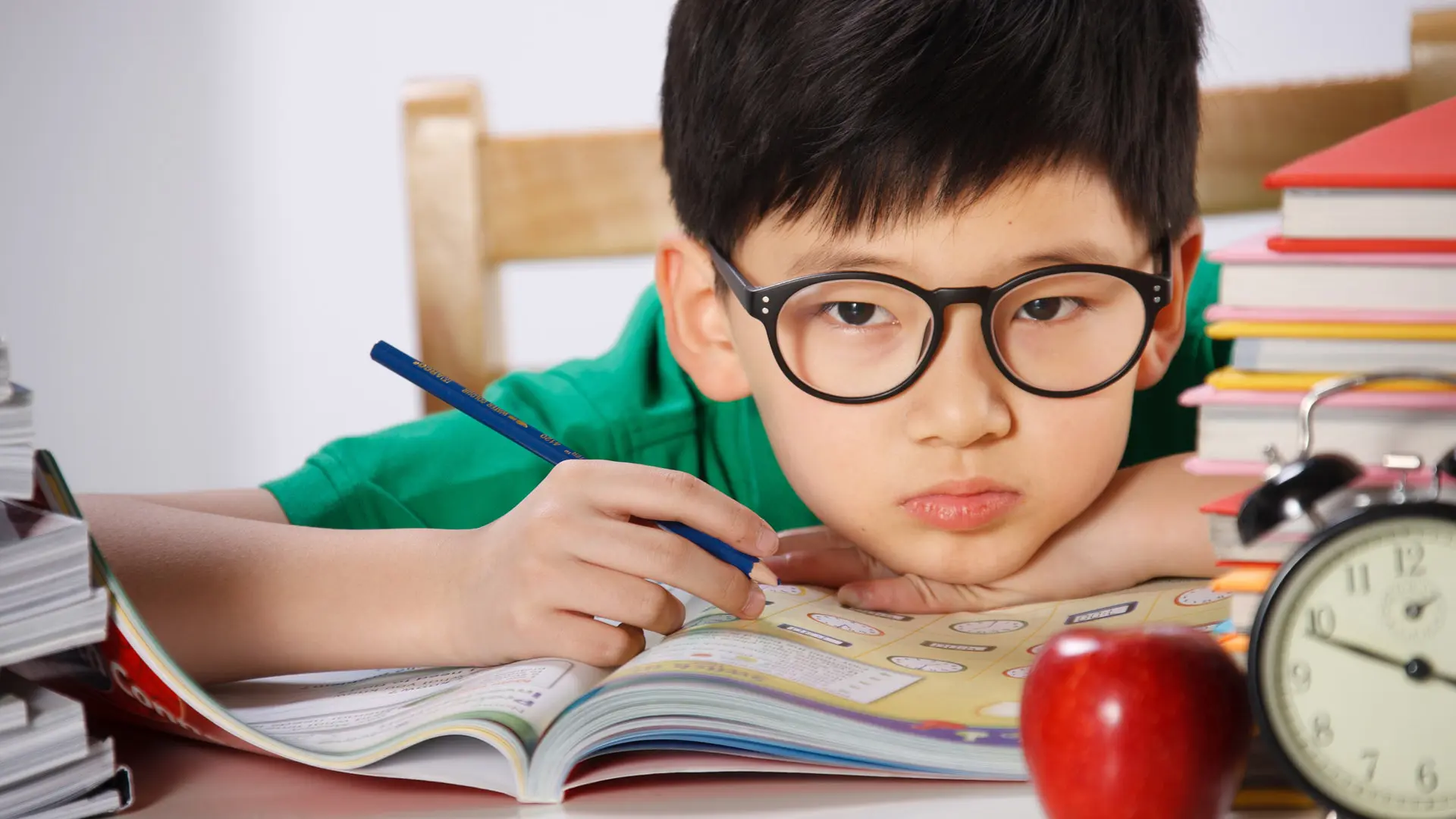

The rate of myopia in children has been rapidly increasing in recent years, becoming one of the most concerning school health issues. However, what worries many parents and experts even more is the significant disparity between children living in urban areas and those in rural regions. According to surveys by the Central Eye Hospital and specialized studies, the rate of myopia among children in urban areas can be twice or even three times higher than that of children in rural areas.

This is not a coincidence. Behind those numbers lies a chain of causes related to living environment, lifestyle habits, academic pressure, and access to technology. This article will specifically analyze the factors that are threatening the vision of urban children, while also offering scientific insights and advice from ophthalmologists to help improve this situation.

School Myopia – A Disease of the Urbanization Era

While many childhood illnesses are being effectively controlled thanks to medical advancements, myopia—especially school-related myopia—is on the rise, particularly in major cities. Statistics from school-based vision screening campaigns paint an alarming picture. Among children aged 6 to 9, the rate of myopia in urban areas has exceeded 20%. By ages 10 to 12, this figure climbs to nearly 40%. And by ages 13 to 15, nearly half of all students in urban areas are wearing glasses.

In contrast, in rural regions, the myopia rates for the same age groups range from only 10% to 25%.

This gap cannot be explained by genetics alone. Instead, the living environment—such as lighting conditions, time spent outdoors, and the extent of screen exposure—plays a decisive role.

Lack of Natural Light – One of the Leading Culprits

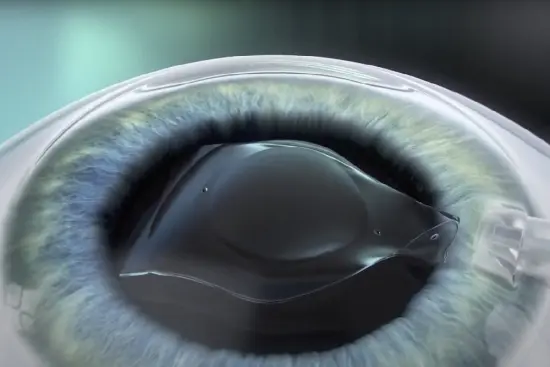

A key factor identified by ophthalmic researchers is the lack of exposure to sunlight. Numerous international studies—including research from the National University of Singapore—have shown that natural light stimulates the retina to produce dopamine, a chemical that helps inhibit excessive elongation of the eyeball. The longer the eyeball, the higher the risk of developing myopia. This explains why children who rarely play outdoors tend to develop earlier and more severe myopia.

In major cities like Ho Chi Minh City or Hanoi, children typically spend most of their time indoors—from enclosed classrooms and tutoring centers to cramped apartment spaces. The average outdoor activity time for urban children is only around 30–60 minutes per day, while the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a minimum of 120 minutes daily.

Electronic Devices and Vision – A Dangerous Connection

The technology boom has brought a surge in electronic device usage among urban children. Smartphones, tablets, laptops, televisions—all create an engaging world but also pose serious risks to children’s eyes.

Blue light emitted from screens not only causes eye strain but also disrupts the body’s circadian rhythm, affecting sleep and indirectly reducing visual quality. Especially when children use devices at close range, for prolonged periods, and without proper breaks, their eyes are forced to accommodate continuously, increasing the risk of accommodative spasm and rapid myopia progression.

A study from Tokyo International University found that children who use electronic devices for more than two hours per day have a 60% higher risk of developing myopia compared to those who use them for less than one hour. In Vietnam, statistics show that urban primary school students now spend an average of 3–4 hours daily on screens—especially during summer holidays or online learning periods.

Academic Pressure and Unhealthy Lifestyles

One factor that cannot be overlooked is academic overload combined with poor study habits. Urban children are often enrolled in extra classes from an early age, facing a constant stream of subjects, tests, and performance expectations. Meanwhile, essential practices—such as proper sitting posture, adequate lighting, and scheduled eye breaks—are frequently neglected.

A large group of Vietnamese schoolchildren in uniform sing or recite together during a school assembly; many of them are wearing glasses, highlighting a high prevalence of myopia.

Many students develop habits such as studying while lying down, leaning too close to their desks, reading under dim yellow light, or studying late at night without breaks. These behaviors all contribute to visual accommodation disorders and significantly increase the risk of refractive errors.

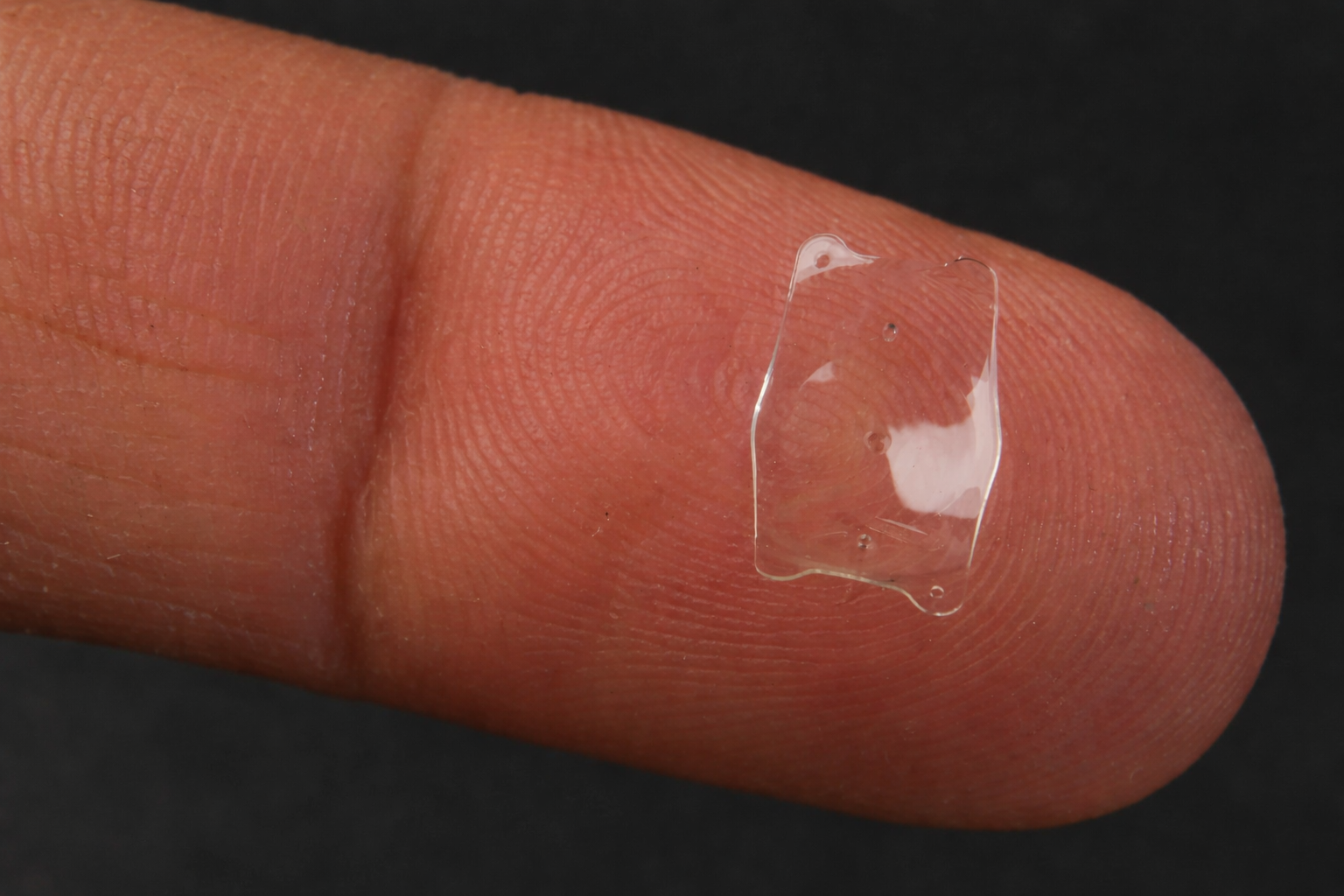

Ophthalmic Perspective: Practical Solutions for Myopia Control

According to ophthalmologists at leading Eye Hospitals, effective prevention and control of school-related myopia—especially in urban children—must begin with fundamental changes in daily lifestyle and living environments.

First, parents should ensure that children spend at least two hours outdoors each day. Activities may include walking, light sports, or simply reading under morning sunlight. Sunlight exposure supports vitamin D synthesis and naturally enhances the eye’s focusing ability.

Second, apply the 20–20–20 rule: after every 20 minutes of near work, have the child look at something 20 feet (6 meters) away for at least 20 seconds to relax the eyes.

Third, limit screen time and prioritize creative or physical activities. Installing blue light filters or enabling night mode on digital devices can also help reduce screen-related eye strain.

In addition, parents should set up an ergonomically appropriate study space—with adequate lighting, furniture that fits the child’s height, and no studying while lying down or leaning too close to books.

Last but not least, schedule routine eye exams every six months, even if the child shows no obvious symptoms. Early detection and correction of refractive errors are crucial in preventing rapid myopia progression, especially during periods of rapid growth.

Conclusion

Myopia in children is not just a cosmetic concern or a learning inconvenience—it is a public health issue. If left unchecked, high myopia can lead to severe retinal complications and even blindness in adulthood.

The disparity in myopia rates between urban and rural children is a powerful warning about modern lifestyles: too sedentary, overly dependent on screens, and lacking outdoor engagement. By raising awareness, fostering healthier habits, and investing in children’s visual health, we can ensure a more vibrant childhood and a clearer future.

vi

vi 27-May-2025

27-May-2025

0916.741.763

0916.741.763 Appointment

Appointment